Interview with Alison Weld by William L. Ellis

Originally Online on Ricco/Maresca Gallery’s FLUENCE

May 24, 2017

|

To label Alison Weld’s colorful, vivid paintings as simply abstraction is like calling the work of Martín Ramírez just drawings. The rich layering of paint with mixed media in her canvases welcomes several conversations at once, and for decades she has operated in an intersectional space of female tropes, the self-reflective narrative, and the spiritual purity of the painted surface.

Born in Fort Knox, Kentucky to a father who was a Korean War medic, Weld moved with her family first to Buffalo, New York, then to nearby Rochester. She later got her undergraduate degree at the SUNY College of Art and Design (Alfred University) and a MFA at the School of the Art Institute in Chicago, where she also discovered the city’s self-taught artistry. Employing an array of approaches; from gestural abstraction and tachism to assemblage, Weld invites extremes of ritual and impulse, nature and artifice, into her work, all balanced in surprising, multivalent ways through the frequent creation of diptychs and triptychs. Among more than two-dozen solo exhibits was a 2010 retrospective at the Art Museum of the University of Memphis, whose Director and curator, Leslie Luebbers, praised Weld for her authentic voice, one that achieves formal mastery and yet at the same time can hold in tension opposing visual elements and ideas. |

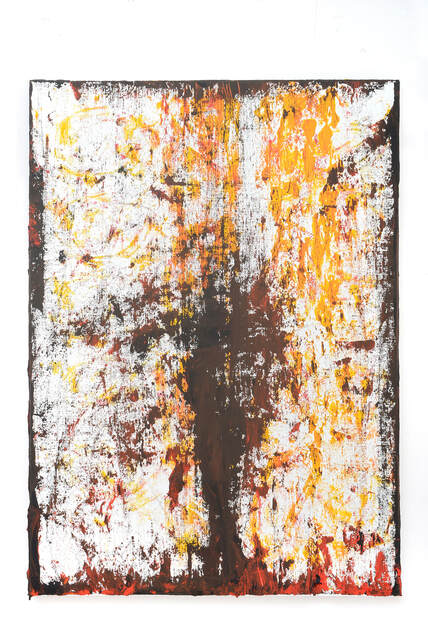

Alison Weld, Meiolania Quartet, 2015, oil, 90 x 78 inches Jersey City Studio

Alison Weld, Meiolania Quartet, 2015, oil, 90 x 78 inches Jersey City Studio

Alison Weld: I knew when I was probably 14 if not younger that I wanted to be an artist. Once a month, the family would go to Buffalo, New York, to see my mother’s mother. I come from a large family – I’m one of six children. And most of the family would go to the zoo. But my mother – who painted – and I would go to the Albright-Knox [Art Gallery]. We wouldn’t walk around together. We both would walk around separately. And she would just go like that [gestures with finger] and point to a piece. So I was raised looking at masterpieces of modern art. They had a Clyfford Still show when I was 13. That was one of the places that Still allowed a museum to show his work. And we also went to the Memorial Art Gallery at the University of Rochester. My mother was in their summer show called the Clothesline Festival. I would look at the other outdoor booths, and I would judge the exhibiting artists. I was a critic because I went to the Albright-Knox and Memorial Art Gallery!

WLE: Your mother did representational painting?

AW: She was a landscape painter, oil.

WLE: How did you develop your fascination with diptychs and triptychs, which has a strong religious connotation?

AW: My work has always been spiritual. When I was young, I was deciding between being a minister and being an artist. And I thought I should be an artist because there were very few female ministers. I just felt art was better for me. I wanted to have one of my paintings on the altar of a church instead of Jesus Christ! [Laughs] As a young artist!

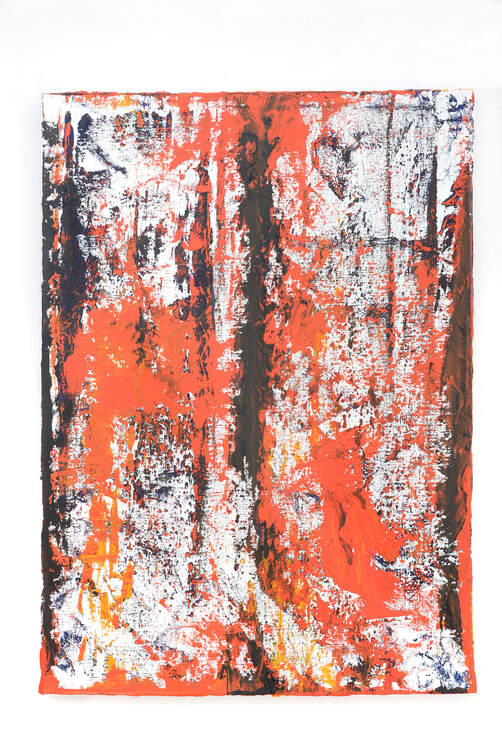

Alison Weld, Adirondack Oratorio 2, 2017, oil on linen, 50 x 36 inches

Alison Weld, Adirondack Oratorio 2, 2017, oil on linen, 50 x 36 inches

WLE: My thought about your work is that abstraction is your religion.

AW: Yes. I think abstraction is my religion. And I think aesthetics is my religion, just looking at art and communing with it. The diptychs started because I didn’t want to be considered whatever I would [otherwise] be, a fourth or fifth [generation] abstract expressionist painter. I wanted to be contemporary and part of the New York art world. I wanted a symbol of my home economics seventh and eighth grade class, a symbol of the domestic history of the female, a symbol composed of the anonymous piece of fabric compared to an oil painting. And I worked on that diptych series from early 1994 to, with the ones with flowers, to 2006. I started the flower juxtapositions in 2003. Now I’m thinking, with this new Liminal series, that this original technique of dealing with the monotype is every bit as, if not more, edgy. But I don’t think about edgy these days. I just think about making a profound piece.

WLE: Explain the idea behind your Tonal Variation series, begun in 2015.

AW: I’m making an assemblage changing the orientation of the original work. And I’m assembling it from other works throughout my history of painting. So they are variations on the originals.

WLE: And autobiographical.

AW: Yeah. I will add new panels, new oils or acrylics, but it is about being in your sixties and assessing. I have so much work because I don’t have children. My works are my children and grandchildren. It really is autobiographical to organize earlier works that were just in storage and to put them up in 2015, ’16 and ’17 anew.

AW: It is a departure. I don’t think it’s transitional. I just think it’s a new series. But I think I will try to make some assemblages out of these as well, but I want it to be all from Liminal and see what that will be like.

WLE: Liminal speaks to you trusting your abilities as an artist, not having to overthink, just letting the process be what it’s going to be without some of the more overt tropes of your earlier pieces. Explain the process.

AW: I create a canvas that I want to have a pressed demeanor. I press it. I move it. I try to create structure by pressing it four times. And I try to have thick paint along the edges so I can also create structure. [In a way] it is the equivalent of my Home Economics diptych structure, but it’s within one canvas. And I love retaining the white of the linen. … I feel as if these are really feminine in that they are so delicate and in keeping the white ground of the linen.

WLE: Given the many pieces you re-visit, how do you know when a work is done?

AW: I know a work is done when the nagging on my consciousness stops. Even if the work is new like this Liminal series, I look at an area and think that isn’t poetic enough or that’s not speaking enough. You know when it’s done.

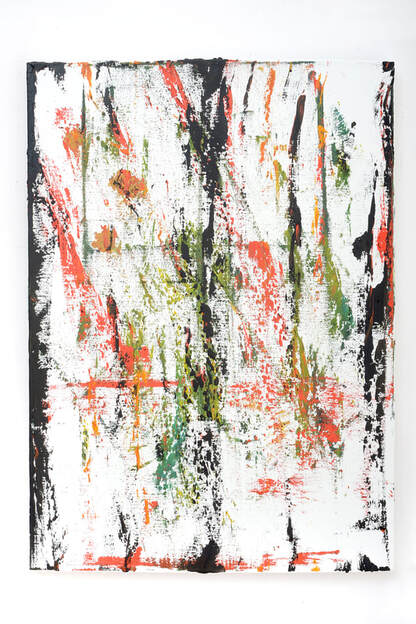

Alison Weld, Adirondack Oratorio 3, 2017, oil on linen, 50 x 36 inches

Alison Weld, Adirondack Oratorio 3, 2017, oil on linen, 50 x 36 inches

AW: In 1977, when I was a graduate student at SAIC (School of the Art Institute of Chicago) Lee Godie would sit or stand with her works near the museum, and students would gather around her. I bought two Lee Godies for twenty dollars a piece! She would sign her name “Lee Godie, French Impressionist.” She was wonderful. Then in art history class at SAIC I learned about Joseph Yoakum. I love his landscapes. I’ve always felt as if all art is self-taught, because the art is of the self, and that’s what you transmit. When I look at the history of figuration, I look for its abstraction. I see El Greco’s self by looking at his color juxtapositions and the sight lines. And so I feel as if I’m seeing his self more than the figuration allows me to see.

WLE: How do you balance your training with the more intuitive aspects of your art?

AW: My painting has been formal as well having as the original mark, the personal mark – abstraction as soulful, as self. My premeditation is in buying the colors and choosing the palette and having the color juxtapositions predetermined.

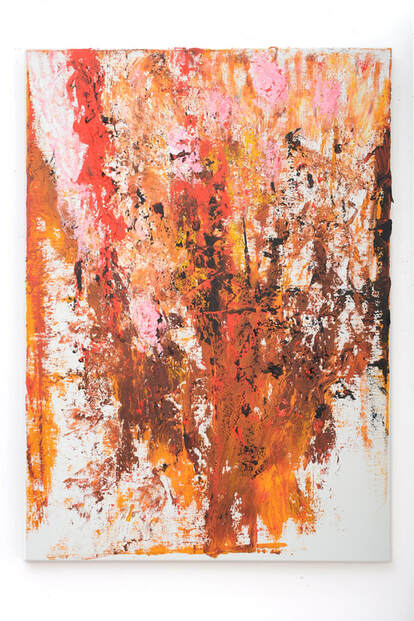

Alison Weld, Adirondack Oratorio 4, 2017, oil on linen, 50 x 36 inches,Jersey City studio

Alison Weld, Adirondack Oratorio 4, 2017, oil on linen, 50 x 36 inches,Jersey City studio

AW: Yes, self-reflection. Thinking about your entire life as an artist. And that’s what the Tonal Variation series is about. They are really self-portraits in that they are a retrospective. They assemble works from as early as 1982 throughout time. So [work from] 1982 and 2000 might be in one piece. So it is self-reflection. Just being able to look at an assemblage and see what you did when you were in your twenties or thirties.

WLE: It becomes its own curatorial process.

AW: Yes.

WLE: What have you learned going through this process?

AW: I think I learned that I believe in pure painting in that I don’t need a fabric panel to talk about society, which the fabric panels did in Home Economics. That I can talk just as much about me being a woman artist born in 1953 just with pure paint.

WLE: Helen Frankenthaler would probably agree.

AW: Exactly!

Other Interviews, Reviews, and Essay Excerpts

Abstract works thoughtful, spontaneous

A review of Art Is My natural World: Alison Weld, 1980 -- 2009

By Bill Ellis

So awash in color are the canvases of Alison Weld, you want to dive right in. Take the art-versus artifice work “Tiepolo’s Dream,” where an abstract painting bursting with hue feels more organic and “natural” than the panels of flower-motif fabric beside it. Or the literal invitation to sit and partake in ‘Ocean Scan,” which offers a beachside view—plastic mat and rock included- of an acrylic splashed picture that equates, with wry postmodern gesture, a trip to the seaside with a trip to the museum.

…According to director Leslie Luebbers, who says that the artist was chosen not only for her mastery of form but also for how she juxtaposes an often-conflicting set of ideas and technique in her work. Weld comes from a place where “intuition, authenticity and all those things are really important,” Luebbers says.

Weld has said as much, adding that the point is to engage the viewer in a “process of seeking and discovery.” Many of her pieces come in the form of diptychs and triptychs, and the ritualized connotation of such structures, often associated with European sacred art, is intentional: color and abstraction are Weld’s religion.

an excerpt from the exhibition catalogue The Tenacious Gesture of Alison Weld,

Rutgers University, Paul Robeson Gallery, 2008.

For an artist, art can begin with a glimmer of a concept and it may conclude with a manifested expression. An artwork may be as simple as a gestural mark on paper, or as complex as an unconventional assembly of seemingly disparate elements. All in all, holding true to Newtonian physics, the energy remains constant and it is just the form that changes. Alison Weld’s imagination and careful contemplation of her artistic output has guaranteed her success. Every action is the result of thought on both conscious and unconscious levels. …Her tenacity is evidenced not only by the longevity of her practice, but also by the sheer range of her work. The drawings Pulled Paint and Pounded Mark in particular demonstrate a concrete relationship to the tomes of recorded art history, starting with the early 1900s, the time of Dada and Surrealism, where the automatique impulse defined the creative act. Throughout this exhibition, an awareness of the gesture provides a legend by which to read the works.

The gathered artifacts that emerge in her sculptural pieces range from the detritus of the natural world (rocks dispelled by the earth, bones bleached by the sun) to symbolically laden plaid fabric. The spontaneous associations that occur seem almost effortless in their impromptu nature. In a sense, the final artworks appear to be apparitions, fleeting glimpses of her psyche, objects fixed but for a moment so we may appreciate their beauty. Their contradictory nature makes them difficult. They are confounding expressions. The sculpture defies linear conclusions, requiring a jumping glance across and around the surface, and time to digest the startling contrasts.

…Weld views her work as testament to her life well spent. Choosing an alternative path to that suggested by her more traditional upbringing, for her creating artwork has been an all consuming passion…one that renews rather than depletes energy sources.

an excerpt from the exhibition catalogue The Tenacious Gesture of Alison Weld, 2008.

Alison Weld builds her imagery through an intense conversation, one that considers the physical, emotional, and ephemeral history of influence. Taking an inventory of historic styles, the artist joins her attention to line and motion—as in the gesture of the abstract expressionists—and her interest in artificial objects and materials that reveal much about contemporary life. Painting with conviction, each gesture in her work becomes its own narrative force.

Weld has been described by art historian Donald Kuspit as “not merely a clever postmodernist” but in fact a voice that reminds us of our fascination with the contradictory nature of humanity, the repetition of physical and representational forms and the cyclical movement of history. This fascinating mix is perhaps nowhere more evident than in Good Saints how I feared and Coifed Sisterhood, both 2008. In both these works, the artist juxtaposes her painted diptychs with found objects that include two previously existing works of art—the kind one might find at a thrift store. This interest in the mass produced, perhaps “low brow” objects is a constant, surfacing again in her floor sculptures. As parallels to the painted works Ms. Weld’s floor sculptures also make dialogical allusions filtered pleasingly through found objects and references to popular culture. Reading the layers together evokes a wonderful abridged history of American culture.

…A serious consideration of society and art history, of abstract and iconic subjects, of the created and found object lies beneath all of Alison Weld’s work. With depth and wit, she explores the relationship of the natural world to the artificial object and the role of humankind in bridging these two. Through her painting, Ms. Weld maintains a dialogue with the history of literary figures, artists, feminists and others who profoundly changed the world. She connects to these icons through her constructed works that ultimately link painting with the social, physical and historical worlds.

an excerpt from the exhibition catalogue The Tenacious Gesture of Alison Weld, 2008.

The Sculptural Juxtapositions of Alison Weld are confounding works of art. They are at once unique and mysterious creations, yet they are strangely familiar, highly evocative, uncanny testaments to profound if hidden yet known truths.

…We certainly recognize them as contemporary artworks which assume their place within an established postmodern discourse at the turn of this new century. They reach back, of course, to the great developments of twentieth century modernist and postmodernist art, most notably the establishment of collage and assemblage as defining aesthetic strategies and to the revitalization of the power of abstraction within the Western tradition. As collages, these structural juxtapositions bring together fragments of seemingly separate realms of meaning: on the one hand they are vestiges of organic life, remains of the natural that seems to have receded from the contemporary urbane consciousness of the art world. On the other hand, they thrust themselves into view as rude intruders from the pop material culture of modern, urban, multi-cultural life fast upon us. Yet they also announce—through the quietly expressive marks of the painter’s media and the visually sophisticated composition of each whole—the presence of a fully self aware contemporary artist.

…Weld’s art offers an opportunity to recall what has been all too occluded in contemporary art: its ancient connection to the spiritual, to the religious impulse which is nothing but that self-same craving for existential connection and meaning. These simple orderings may be seen as offerings placed before the immensity of the world. They display what the artist has made of the given world, what she has found, treasured, created and given back in evidence of her engagement with life.

Radford University Art Museum, Virginia

Alison Weld is a very humorous artist.

She is also a very thoughtful artist.

Weld has spoken of “feminizing abstract expressionism.” The gestural vigor of her palette knife-and brush work roots the works in the body; but so do the artificial animal pelts to which the painterly is contrasted . . . Seen from this angle, the uninflected swatches of machine-made fur poke fun at the “all-over” quality for which Abstract Expressionist paintings were praised. Recently, Weld has moved the faux fur from the wall to the floor, establishing horizontal fields onto which she places found objects: rocks, animal skulls, photographs. Jackson Pollock famously dripped his paint on unstretched canvas lying on the floor, but when he was finished, the work went (back) on the wall. Weld is content to leave her works on the floor, creating tableax that may echo her many years’ experience working in natural history museums.

It’s a somewhat startling, eye-blinding–certainly eye unsettling–juxtaposition: on the one hand an abstract expressionistic painting, full of powerful, explosive gestures–at once strong-willed and spontaneous, indeed aggressively spirited–and flashing colors, adding to the overall excitement and intensity and on the other side, a usually more subdued, if still sensuously seductive–and often texturally provocative (if in a different way than the expressionistic painting) fabric surface, sometimes inscribed with an imagistic pattern. Errand into the Wilderness, 1995, Love Supreme, 1996, Psyche’s Soul, 1997 and Song of Orange, For Mingus, 1997, among many other diptychs, bowled me over with the boldness of their juxtapositions. Reflecting on the experience I realized that it was much more than a matter of the shock of the new–of the daring originality of Weld’s perceptual drama. She has found an unusually fresh way to visually embody psychic conflict–that’s what conceptually engaged me.

The electrifying contradictoriness of the canvases, yet the elusive dialectic generated by their friction–they seemed repelled by each other, but also subliminally “aligned”–symbolizes the divided self, and perhaps its aborted yearning to be whole. Weld is not merely a clever postmodernist, gratuitously contrasting modernist styles, as though suggesting that one is no more valid than any other–pure painting and impure image are equally legitimate modes in her diptychs–but rather reminding us, in no uncertain terms, of an emotional truth we are reluctant to acknowledge. She’s ripped away the veil of amnesia that hides the fact that we are permanently divided against ourselves. Her canvases enact the inner drama of every life through their own militant difference. The diptychs are constructed of opposing styles, which are all art historically familiar, but Weld’s discomforting juxtaposition of them brings out their radical difference, implying that it is impossible to reconcile them, which restores them to unfamiliarity, and with that to emotional credibility. The parts of Weld’s diptychs seem to fall apart yet they remain together, giving the diptychs as a whole a paradoxical integrity.

The Columbus Dispatch, [Ohio] Sunday, April 02, 2006

Painter explores conflicts, contrasts by Christopher A. Yates

Exhibit Springfield Museum of Art [Ohio] Allegories of Strife: The Diptychs of Alison Weld, 1990 - 2005

The work of New York painter Alison Weld centers on conflict, transition and dichotomy.

Reflecting a kind of postmodern identity crisis, her diptychs present opposing states of mind. She juxtaposes smooth, kitschy fabric next to viscous, energetic painting, finding territory somewhere between pop art and abstract expressionism.

Her first significant exhibit in the Midwest has been organized by the Springfield Museum of Art and includes more than 35 paintings and sculptures; the show serves as a small retrospective documenting Weld’s development during the past 15 years…

Many issues emerge but essentially the work is about contrast: male vs. female, natural vs. manmade, internal vs. external and spontaneous vs. controlled. In Love and Romance in the Triassic, Weld pairs a panel of paint-spattered artificial flowers with a gestural Willem De Kooning-like creature. The flowers evoke femininity, while the painting suggests masculine bravado. The work evokes the beginning of the Triassic period about 220 million years ago, during which more than half of the world’s marine, plant and animal species died out. In this light, the image becomes a study of star-crossed lovers, and the flowers suggest funerary ritual.

A similar death theme occurs in Field Study. Next to flower-patterned fabric, a painted image with rhythmic strokes of yellow, red and green suggests growth. The work is light and airy, but Weld’s text reveals that the inspiration came from a weathered pelvic bone. Other pieces were prompted by the poetry of Rainer Maria Rilke and the Persian poet Rumi.

Unexpectedly, enigmatic juxtapositions occur in John Brown and the Hermit Thrush #1 and Errand into the Wilderness, in which fake fur is positioned next to gestural graphic marks. The wilderness becomes a metaphor for things urban and man-made. Weld’s work is visceral and compelling, celebratory and brooding. Pieces such as Psyche’s Soul exert a powerful and almost lyrical feminine presence. Others are darker, prompting consideration of conflict and death. Her diptychs reflect life’s paradigms, in which nothing is absolute and everything is in flux.

HN: I’m very interested in your concept regarding visual philosophy. Can you elaborate on this?

AW: While I embrace visual quality and formal visual elements as necessary to a visual work, I believe that the concept underlying the work is foremost. Art is not decoration. It is idea. It is interpretation. It is created from and physically imbued with big ideas and results from a system of beliefs however idiosyncratic the mix of ideas may be in a particular work. Existentialism, Transcendentalism, a contemporary and somewhat ironic take on the current climate and society now–material culture, pop culture, psychology and gender–are all part of the visual philosophy of my work. I am a visual philosopher. I think and create. I respond to history and to the time in which I live.

HN: I am very intrigued by the juxtaposition of different techniques in your work. Can you explain this dichotomy?

AW: I have been interested in creating tension in my work since my Chicago days as a graduate student. There was tension in my paintings on shower curtains rather than traditional canvases. I have always wanted to challenge tradition while also looking at tradition and continuing it anew. My diptychs, that contrast the vernacular fabric with a more personal oil, speak about the whole self–the individual in society, the emotional and intellectual aspects of a person and as Donald Kuspit says... “the divided self.” I don’t want painting to be precious. I want it to be relevant to today. If the personal is to be considered relevant and profound, it must be of our time, hence the dichotomy.

The Figurative Impulse in Abstraction, Rider University, 2006

Harry I. Naar is Professor of Fine Arts and Gallery Director, Rider University

From Recent Paintings from the Vertebrae Continuo Series by Edith Newhall

Over the past two decades, Weld has become known for a primal, gestural abstraction composed of rich, impastoed color (though one might see the New York School as an antecedent, it is no accident, I think, that she is represented in New York by Robert Steele, who is an expert on Aboriginal painting).

.....The Vertebrae Continuo series seems almost chaste. The white ground surrounding Weld’s rubbed forms gives the works a lucidity and immediacy that recalls Joan Mitchell’s paintings from the nineties, with their super white grounds. But unlike Mitchell’s paintings, Weld’s are born of a slow, almost geological process that begins with oil paint and cold wax applied with a palette knife, over which subsequent layers of oil stick are rubbed.

It would be presumptuous to say that Weld’s new paintings represent a breakthrough for her. They do, however, stand entirely on their own while achieving an effect similar to her multi-panel work. Instead of taut man-made fabric flush against a painted surface, the startling juxtaposition here is the pulsing, flamboyant form adrift in a sea–or better, a sun-bleached desert–of white. Nothing feels extraneous. These “pure” paintings are simultaneously commanding and effervescent, archaic and new. Excerpt from the exhibition brochure, Recent Paintings from the Vertebrae Continuo Series, Robert Steele Gallery, 2005 Edith Newhall is a Philadelphia based art critic and a former staff writer for New York Magazine.

The compelling art of Alison Weld depends upon the recognition that materials can be seen as ends in themselves . . .

One can see how the New York School's emphasis on the physical integrity of paint and the intuitive self is taken up again in her paintings which celebrate the physicality of materials in frank and open ways . . .

Weld establishes the language of gesture through the bold use of paint as material; her panels of thickly impastoed paint take gesture as the basis of art. But then she does something quirky and very contemporary: she juxtaposes another panel, created with a different material - fake fur, vinyl, artificial flowers - which she uses to comment, formally and metaphysically, on the lush expressionism of the painted panel . . .

It would appear that artifice is important to Weld because integrity is important as well, and that distinguishing between the two is intended to create a contemporary, as opposed to an historicist or traditional self. It is to Weld's credit that her intelligence seeks out not one but two kinds of being.

William Paterson University, Wayne, NJ, 2003.

Jonathan Goodman is a poet and arts writer based in New York City.

Through suggestive, haptic counter-balancing of configurations, [Alison] Weld constructs a world as no other painter. It is the riveting play of contrasts that gets to you, the invitation to assign value. In her works juxtaposition raises its head on every level: proportion, texture, weight, even smell seems magnified, almost exalted. The artist is a wizard of antinomies when it comes to the play of surfaces and their associations . . .

[The artist's] mongrel fusion between fabric and its phenotype, between handmade and gesture, lets through the codes of expressionism. In a strange and miraculous way, the values of sincerity are re-assessed through the guileless (im)purity of mass production . . . Weld involves us in time traveling, as we hurl through the history of styles, fashion and taste. She has a yen for surfaces and ornamentation that recall certain time periods or activities: ab-ex and neo-ex intervene with the retro look of fake green fur, interface with soft pliable satiny-sheened vinyl or luxuriate with a meretriciously fake alligator-pebbly surface. Weld investigates how meaning is constructed.

Molloy College Art Gallery, Rockville Centre, LI

The irony of Ms. Weld’s approach lies in the uneasy marriage of expressionistic and mass-produced abstractions. The former are deliberately subjective and hard to decipher; the latter are instantly recognizable and familiar. The result is a kind of intellectual game in which high and popular art compete on a playing field leveled by the artist.

From Forces From the Soul of a Dyed-in the-Wool (Or is it Fake Fur?) Romantic by Barry Schwabsky

Hunterdon Museum of Art, Clinton, NJ

In “The Home Economics Suite,” Alison Weld paints thick, sensual abstractions that she pairs with panels of densely patterned or synthetically shaggy fabrics. The best is called “Song of Orange, for Mingus” (1997), its big-gestured canvas literally troweled with colors (she mixes her oils with wax to add texture) and paired with a rectangle of cotton-candy- pink fur slashed by black zebra stripes.

Born in Kentucky and trained at the Art Institute of Chicago and the Wolverhampton College of Art in England, Weld is a big painter in defiance of fashion: she is someone who wants to live large and you have to hand her her ambition… Moving your eyes from her brimming brushwork to the petroleum-spun sheen of her fabrics is like licking chocolate off a sour ball … and is in some poetic way a very common American experience.

Alison Weld’s intriguing two-panel paintings play with the idea that opposites attract, or more accurately, that opposites can balance and become equivalent. ...Each layer represents a layer of time–the time involved in its creation, the time involved in its re-creation through the gaze of the observer, the time it contains in itself, in its own phenomenological duration. ....The fabrics (pink roses against a faded green-grey ground, faux velvets, striped and stippled faux furs, jazzy yellow and orange shags...that she chooses to complete the work add an edge to the paintings, stretching their identity to relocate them in the here and now of the mass-produced and in the realm of the unique art object. Her use of them is extraordinarily direct; they are necessary to the paintings she is making and match up with the painted panel formally and psychologically, like an alter ego. For Weld, these commonplace fabrics have an appeal in their own right and in the context of her work, they are both transfigured and not, metaphoric and not.

Excerpt from exhibition brochure, Alison Weld, Carlson Gallery, University of Bridgeport; Aljira, a Center for Contemporary Art, 1996

Lily Wei is a New York-based independent critic and curator.